Ethereum Virtual Machine in Rust - Part 5: How to execute a smart contract (1/2)

05 Dec 2018- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 1: Introduction

- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 2: The stack

- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 3: Loops and Pure functions

- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 4: After the stack, the memory

- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 5: Executing a real smart contract

- Ethereum virtual machine in Rust - Part 5-Bis: Executing a real smart contract with Rocket

I need to take a step back from memory models after having written three posts about the stack and the memory. There is still a third way to save data, which is the persistent storage but I think it is about time we try to emulate a real smart contract, from the beginning.

But first of all what happens when an Ethereum peer receives a new message?

A look at Parity code

Parity-Ethereum is a Rust implementation of Ethereum (much more advanced than mine ahah). It is the second most used Ethereum client after go-ethereum according to ethernode.

It is written in Rust, so we can stay in the spirit of this series of article when looking at the source code. An Ethereum client is not only a virtual machine. It deals with many more things such as:

- A peer-to-peer network

- A RPC server for client’s requests

- A consensus algorithm

- The actual blockchain implementation

The codebase is used, but fortunately we are only going to focus on a small part of it. The VM’s interpreter

is at ethcore/evm/src/interpreter/mod.rs. You can find the main loop and the instruction execution in this file. The code is actually quite straightforward and easy to read after practicing Rust a bit.

The function Interpreter<Cost>::new is called to create a new Interpreter.

This function is then called by the EVM factory localed in ethcode/evm/src/factory.rs.

/// In factory.rs

/// Evm factory. Creates appropriate Evm.

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct Factory {

evm: VMType,

evm_cache: Arc<SharedCache>,

}

impl Factory {

/// Create fresh instance of VM

/// Might choose implementation depending on supplied gas.

pub fn create(&self, params: ActionParams, schedule: &Schedule, depth: usize) -> Box<Exec> {

match self.evm {

VMType::Interpreter => if Self::can_fit_in_usize(¶ms.gas) {

Box::new(super::interpreter::Interpreter::<usize>::new(params, self.evm_cache.clone(), schedule, depth))

} else {

Box::new(super::interpreter::Interpreter::<U256>::new(params, self.evm_cache.clone(), schedule, depth))

}

}

}

}

That’s cool. Now we can check wherever this factory is used to find out what happen when the Ethereum node receives a message. Easier said than done, but by following little by little the source code, you should arrive to a file called executive.rs. An executive is something that is executing (?) and can be of many kind:

- ExecCall

- ExecCreate

- ResumeCreate

- ResumeCall

- Transfer

- CallBuiltin

This rings a bell. I guess ExecCall is used to execute the smart contract when somebody is sending a message. ExecCreate would be

when somebody want to create a smart contract. Anyway, there is a big function call

execthat will match on the kind of Executive and do the appropriate action. In our case, it will execute the following:

CallCreateExecutiveKind::ExecCall(params, mut unconfirmed_substate) => {

assert!(!self.is_create);

{

let static_flag = self.static_flag;

let is_create = self.is_create;

let schedule = self.schedule;

let mut pre_inner = || {

Self::check_static_flag(¶ms, static_flag, is_create)?;

state.checkpoint();

Self::transfer_exec_balance(¶ms, schedule, state, substate)?;

Ok(())

};

match pre_inner() {

Ok(()) => (),

Err(err) => return Ok(Err(err)),

}

}

let origin_info = OriginInfo::from(¶ms);

let exec = self.factory.create(params, self.schedule, self.depth);

let out = {

let mut ext = Self::as_externalities(state, self.info, self.machine, self.schedule, self.depth, self.stack_depth, self.static_flag, &origin_info, &mut unconfirmed_substate, OutputPolicy::Return, tracer, vm_tracer);

match exec.exec(&mut ext) {

Ok(val) => Ok(val.finalize(ext)),

Err(err) => Err(err),

}

};

let res = match out {

Ok(val) => val,

Err(TrapError::Call(subparams, resume)) => {

self.kind = CallCreateExecutiveKind::ResumeCall(origin_info, resume, unconfirmed_substate);

return Err(TrapError::Call(subparams, self));

},

Err(TrapError::Create(subparams, address, resume)) => {

self.kind = CallCreateExecutiveKind::ResumeCreate(origin_info, resume, unconfirmed_substate);

return Err(TrapError::Create(subparams, address, self));

},

};

Self::enact_result(&res, state, substate, unconfirmed_substate);

Ok(res)

},

That’s a bunch of complicated code. But what is it telling me is that a new VM is created for each call, and that the parameters of the call are passed to the

VM in self.factory.create. I won’t dig further in Parity code. It is very interesting to explore but also a bit overwhelming. What I learned from there

is enough for now. Basically when the node receives a message, it will:

- extract the parameters from the message

- Create a new VM (memory and stack empty) with the message parameters.

- Start executing the code in the VM from the first instruction

The VM starts with an empty stack and memory, but the storage is persistent so it will be in the same state as after the last contract’s execution.

The message’s parameters are also injected in the VM. You can retrieve them using specials opcodes: CALLDATALOAD, CALLDATASIZE.

Dissecting a smart contract

Instead of just executing a few selected instructions, in this part I am going to follow a compiled solidity contract from the beginning.

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Example {

uint x;

function takeOver(uint y) public {

x = y;

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {

x = a * b;

}

}

Now, let’s take a look at this smart contract binary. We have:

/* "contract.sol":25:196 contract Example {... */

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

jumpi(tag_1, lt(calldatasize, 0x4))

calldataload(0x0)

0x100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

swap1

div

0xffffffff

and

dup1

0x165c4a16

eq

tag_2

jumpi

dup1

0xab1f3be2

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_1:

0x0

dup1

revert

/* "contract.sol":127:194 function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {... */

tag_2:

callvalue

/* "--CODEGEN--":8:17 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

iszero

tag_4

jumpi

/* "--CODEGEN--":30:31 */

0x0

/* "--CODEGEN--":27:28 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":20:32 */

revert

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

tag_4:

/* "contract.sol":127:194 function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {... */

pop

tag_5

0x4

dup1

calldatasize

sub

dup2

add

swap1

dup1

dup1

calldataload

swap1

0x20

add

swap1

swap3

swap2

swap1

dup1

calldataload

swap1

0x20

add

swap1

swap3

swap2

swap1

pop

pop

pop

jump(tag_6)

tag_5:

stop

/* "contract.sol":66:121 function takeOver(uint y) public {... */

tag_3:

callvalue

/* "--CODEGEN--":8:17 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

iszero

tag_7

jumpi

/* "--CODEGEN--":30:31 */

0x0

/* "--CODEGEN--":27:28 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":20:32 */

revert

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

tag_7:

/* "contract.sol":66:121 function takeOver(uint y) public {... */

pop

tag_8

0x4

dup1

calldatasize

sub

dup2

add

swap1

dup1

dup1

calldataload

swap1

0x20

add

swap1

swap3

swap2

swap1

pop

pop

pop

jump(tag_9)

tag_8:

stop

/* "contract.sol":127:194 function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {... */

tag_6:

/* "contract.sol":186:187 b */

dup1

/* "contract.sol":182:183 a */

dup3

/* "contract.sol":182:187 a * b */

mul

/* "contract.sol":178:179 x */

0x0

/* "contract.sol":178:187 x = a * b */

dup2

swap1

sstore

pop

/* "contract.sol":127:194 function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {... */

pop

pop

jump // out

/* "contract.sol":66:121 function takeOver(uint y) public {... */

tag_9:

/* "contract.sol":113:114 y */

dup1

/* "contract.sol":109:110 x */

0x0

/* "contract.sol":109:114 x = y */

dup2

swap1

sstore

pop

/* "contract.sol":66:121 function takeOver(uint y) public {... */

pop

jump // out

That’s a lot to swallow. I am going to split it a bit so that this code is easier to understand. Let’s start with the first lines:

/* "contract.sol":25:196 contract Example {... */

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

jumpi(tag_1, lt(calldatasize, 0x4))

calldataload(0x0)

0x100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

swap1

div

0xffffffff

and

dup1

0x165c4a16

eq

tag_2

jumpi

dup1

0xab1f3be2

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_1:

0x0

dup1

revert

The first instruction mstore(0x40, 0x80) is actually storing the free memory pointer address in memory.

jumpi(tag_1, lt(calldatasize, 0x4)) will move to tag_1 if the size of the input data is too small.

If that’s the case, the contract will abort (revert).

If not, the input data is pushed on the stack (calldataload).

The rest of the code is a bit unclear. Some operation is done with the input data (DIV, AND), and then the result

is compared against 0x165c4a16 and 0xab1f3be2. If it is equal to the first value, then the code at tag_2 will

be executed. If it is equal to the second value, the code at tag_3 will be executed. If you look at tag_2 and

tag_3, you’ll notice that these are our two functions of the smart contract.

This piece of assembly code is just routing us to the correct function based on the input data. Before digging a bit

more, I want to take a look at the rest of the assembly code generated by solc (actually, the detail of that

calculation will be done in the next article). Let’s follow tag_2.

tag_2:

callvalue

/* "--CODEGEN--":8:17 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

iszero

tag_4

jumpi

/* "--CODEGEN--":30:31 */

0x0

/* "--CODEGEN--":27:28 */

dup1

/* "--CODEGEN--":20:32 */

revert

/* "--CODEGEN--":5:7 */

tag_4:

/* "contract.sol":127:194 function multiply(uint a, uint b) public {... */

pop

tag_5

0x4

dup1

calldatasize

sub

dup2

add

swap1

dup1

dup1

calldataload

swap1

0x20

add

swap1

swap3

swap2

swap1

dup1

calldataload

swap1

0x20

add

swap1

swap3

swap2

swap1

pop

pop

pop

jump(tag_6)

tag_5:

stop

/* "contract.sol":66:121 function takeOver(uint y) public {... */

The snipped ends with a jump to tag_6, which is the body of the function multiply. The snippet of code here

is just extracting data from the input parameters:

callvaluewill copy the Wei sent to this contract to the stack- If callvalue is 0, the contract will

revert, else it will jump totag_4 - A bunch of instructions are done with

calldataloadto pushaandbon the stack.

In detail:

pop

tag_5

[tag_5]

0x4

[tag_5, 0x4]

dup1

[tag_5, 0x4, 0x4]

calldatasize

[tag_5, 0x4, 0x4, data_size]

sub

[tag_5, 0x4, data_size-0x4]

dup2

[tag_5, 0x4, data_size-0x4, 0x4]

add

[tag_5, 0x4, data_size]

swap1

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4]

dup1

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, 0x4]

dup1

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, 0x4, 0x4]

calldataload

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, 0x4, data(offset=0x4)]

swap1

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, data(offset=0x4), 0x4]

0x20

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, data(offset=0x4), 0x4, 0x20]

add

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, data(offset=0x4), 0x24]

swap1

[tag_5, data_size, 0x4, 0x24, data(offset=0x4)]

swap3

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), 0x4, 0x24, data_size]

swap2

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x24, 0x4]

swap1

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, 0x24]

dup1

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, 0x24, 0x24]

calldataload

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, 0x24, data(offset=0x24)]

swap1

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, data(offset=0x24), 0x24]

0x20

add

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, data(offset=0x24), 0x44]

swap1

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data_size, 0x4, 0x44, data(offset=0x24)]

swap3

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data(offset=0x24), 0x4, 0x44, data_size]

swap2

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data(offset=0x24), data_size, 0x44, 0x4]

swap1

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data(offset=0x24), data_size, 0x4, 0x44]

pop

pop

pop

[tag_5, data(offset=0x4), data(offset=0x24)]

jump(tag_6)

In these two snippets of assembly code, we saw how the calldataload, calldatasize instructions

were used to push the input data on the stack. calldataload is also used to find out what

function to execute in our smart contract. There is still a missing piece though. How is the input

data sent to the smart contract? How is it loaded? How do we map the value 0x165c4a16 to the correct

function?

Input data in detail

Phew, that’s a lot of assembly code. We encountered a few mysteries on our way:

- Why are we checking that input data size is less than 4?

- How do we find out the label for the function to execute?

- How do we get the function parameters?

But first of all, what kind of input data do Ethereum clients send? I’ll refer to this link.

Hum, unfortunatly, not much digging is required here :) The input data consists of the function to execute, plus the required parameters. They will be packed in one hexadecimal string which contains the encoded values. More details are available in Solidity documentation.

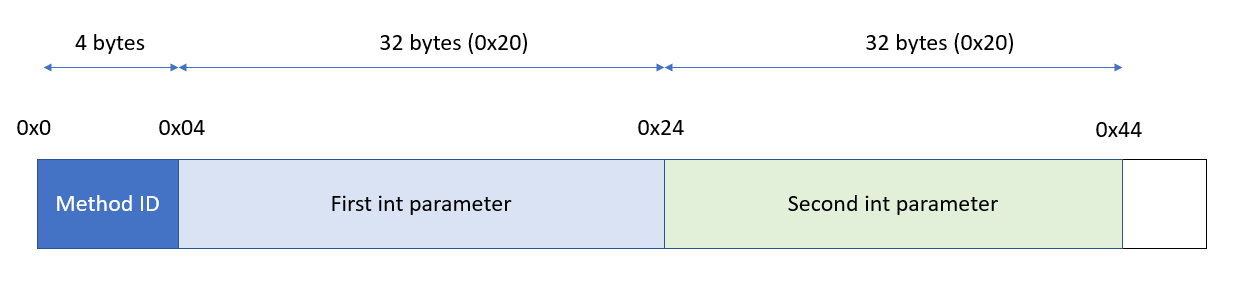

To summarize, the method ID is created by taking the first 4 bytes of the Keccak hash of the function’s signature. Then, the arguments are added to the string. In the case of our integer, they will be converted to their hexadecimal form, padded 32 bytes (256 bit, size of the EVM word). In the binary code, we check that the input data size if at least 4! This is because we need to get the method ID. Then, the method ID is extracted using some bytes operations.

Now, take a look at the following image. It explains all our calls to CALLDATALOAD.

First, we get 32 bytes from index 0x0 (CALLDATALOAD(0x0)). It includes our method ID and a bit of the first parameter so we need to extract only 4 bytes. This is done by dividing by (1 « (29*8)) and extracting the 4 first bytes with (AND 0xFFFFFFFF). I wonder

why the code didn’t compile to a right shift only here. Maybe the optimized version is doing that. Then, we get the first parameter with CALLDATALOAD(0x4) and the second parameter with CALLDATALOAD(0x24). After that, it is business as usual!

Model the input data and CALLDATALOAD/CALLDATASIZE in our VM

The input data is, as we saw, just a byte array that return words. The following can be used.

use self::uint::U256;

pub struct InputParameters {

data: Vec<u8>,

}

impl InputParameters {

pub fn new(data: Vec<u8>) -> InputParameters {

InputParameters { data }

}

pub fn get(&self, index: usize) -> U256 {

self.data[index..index+32].into()

}

pub fn size(&self) -> U256 {

U256::from(self.data.len())

}

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::*;

#[test]

fn test_parameters_ok() {

let data = (0..32).collect();

let params = InputParameters::new(data);

let size = params.size();

assert_eq!(32, size.as_u32());

let bigint = params.get(0);

assert_eq!(31, bigint.byte(0));

assert_eq!(0, bigint.byte(31));

}

}

Then, the VM itself needs to be modified to accept InputParameters as input data. We also need to add the opcodes

and implementation of CALLDATALOAD and CALLDATASIZE.

use params;

pub struct Vm {

pub code: Vec<u8>, // This is the smart contract code.

pub pc: usize,

pub stack: Vec<U256>,

pub mem: Memory,

// Parameters received in the message

pub input_data: params::InputParameters,

// detect if code ended.

pub at_end: bool,

}

impl Vm {

pub fn new_from_file(filename: &str, input_data: params::InputParameters) -> Result<Vm, Box<Error>> {

let mut f = File::open(filename)?;

let mut buffer = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut buffer)?;

let code = decode(&buffer)?;

Ok(Vm { code: code, pc: 0, stack: Vec::new(), mem: Memory::new(), input_data, at_end: false})

}

// ...

Opcode::CALLDATASIZE(_) => {

let size = self.input_data.size();

self.stack.push(size);

},

Opcode::CALLDATALOAD(_) => {

// This is a bit dirty. As first approximation, there is not

// way we would have a size larger than 32 bits. Lets try it

// and if it fails, it will panic (which is what I want)

let idx = self.stack.pop().unwrap().as_u32() as usize;

let data = self.input_data.get(idx);

self.stack.push(data);

},

// ...

This article is getting quite long so I’ll stop here. In next article, I am going to write EVM code in assembly that should read input data and execute it using my VM. Then, I’ll take a look at the persistent storage. There is still so much to explore and I’ve only taken a look at the EVM…